Do workers follow norms of reciprocity in the labour market?

After more than 10 years since data collection, my research has been published in Management Science

After what have been troubled years in my research career, it’s a great joy to have finally published in what is probably the most prestigious economics journal I have achieved so far. The article “No gifts returned: Surprise Bonuses Reduce Productivity in a Natural Field Experiment ” is just out in Management Science. Here is the postprint of the article.

In 2014, when I travelled to Colombia to carry out the fieldwork for this and another project, I had already started slow-travelling to faraway places to reduce my carbon emissions. I want to thank Dennis Snower, former President at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW), who allowed me to travel 8,000km by cargo ship to reach Colombia from Europe.

This research attempts to study the implications of a fundamental facet of human psychology, that is, reciprocity, and its implications for the labour market. Reciprocity is the tendency to respond to generous actions with generosity and to spiteful actions with spite, even if (and especially if) this goes against one’s self-interest – narrowly defined. The fundamental role of reciprocity in archaic societies was first identified by French sociologist Marcel Mauss in the seminal essay “The gift”. But its importance is still current. In many aspects of our lives, we see people willing to sacrifice their personal interest to reward others acting for the common good and to punish those acting against it, sometimes even endangering their own lives. This motivation is partly spurred by the willingness to acquire prestige and a good reputation in social interactions, and may thus be framed as delayed self-interest. However, we observe reciprocity also in anonymous and ephemeral interactions where reputation building is impossible. This result must mean that an intrinsic willingness to act reciprocally is also active.

According to Nobel Prize Laureate George Akerlof, reciprocity is also at work in the labour market. Relying on anecdotal evidence, Akerlof argued that a common practice for US firms is to set wages above the market-clearing level. Workers would then respond by raising their productivity above the standard. Akerlof aptly called this a “gift exchange”. In his mammoth ethnographic analysis of managerial practices, Thomas Bewley also stressed the occurrence of reciprocity in the “negative” domain. Workers whose wages are cut below the reference point would react reducing their productivity. The result is that wages are rigid when they have to be adjusted downwards. Therefore, when profits shrink during economic recessions, firms prefer to lay off workers rather than reduce wages. The macroeconomic implications of reciprocity appear, therefore, massive.

A lot of empirical and experimental research has been accumulated to better understand the robustness and conditions of the “gift exchange” in the labour market. You can find a summary in our article. While some research does find support for the gift exchange hypothesis, other experimental research finds that the effect on productivity is transient or fails to find any effect at all. Sometimes, non-monetary “gifts” have a higher productivity impact than monetary gifts.

In our research, we first aimed to ascertain the relevance of gift exchange outside of “WEIRD” societies, where WEIRD stands for Western Educated Industrialised Rich Democracies. As forcefully argued by Joseph Henrich, up to 90% of psychology research has taken place in WEIRD countries. This would be ok if WEIRD countries were representative of psychology worldwide. The problem is that this is not the case. People from WEIRD countries have “weird” behaviour and psychological traits compared to the rest of the world.

We also wanted to deepen our understanding of how the gift exchange works when it introduces inequality in a team. What happens if only one worker in a team receives a pay rise? Will she still reciprocate the manager’s gift? Or will she think that the manager has behaved unfairly to the co-workers who did not receive the bonus, thus thwarting her productivity? How will the worker who did not receive the bonus react? Does the justification of the bonus matter, as, for instance, a bonus based on higher performance may be more acceptable than a purely arbitrary bonus? What is the workers’ reaction if the bonus is allocated to the socially more disadvantaged workers? And what is the overall productivity impact in all these cases?

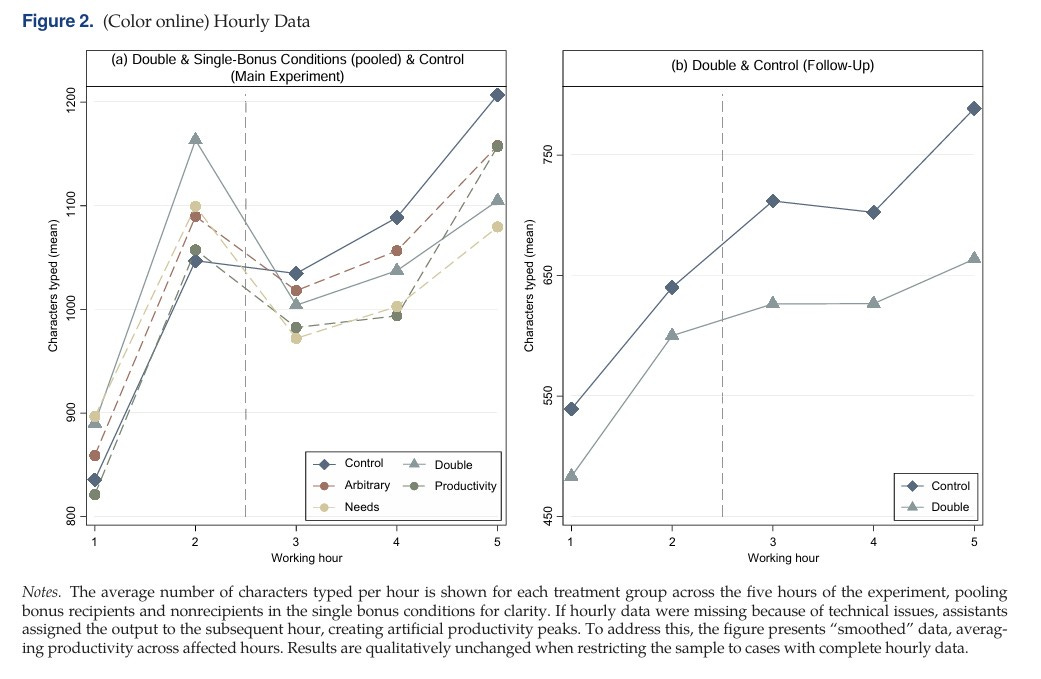

To address these questions, we set up a controlled experiment in which we invited n=302 workers to carry out a one-day data entry task at the University Konrad Lorenz (first wave) and Nacionál (second wave) of Bogotá, Colombia. Our target variable is the number of characters entered into an electronic spreadsheet. Two workers were called each day. They were not informed that they were part of a research study, thus ensuring that the work environment was as close as possible to a “natural” one. In the middle of the day, none, one, or both workers received a bonus payment. When only one worker received the bonus, this was justified based on: (a) higher productivity in the morning session by the recipient; (b) higher social needs by the recipient; (c) purely arbitrarily. Each worker participated in only one condition. As usual in an experiment, you need control conditions acting like placebos to study the impact of the treatment.

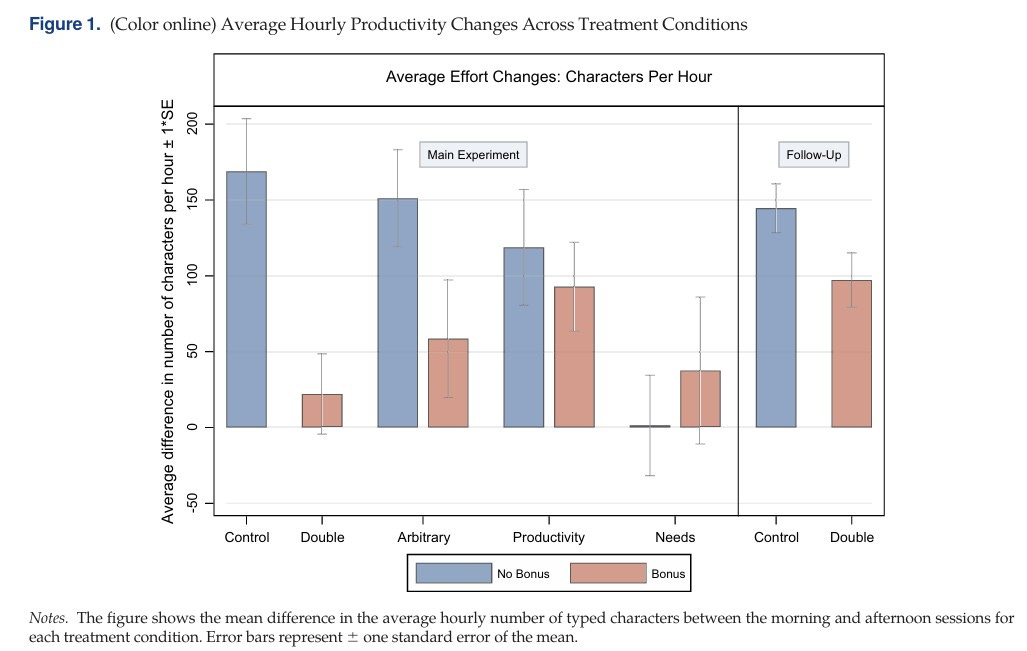

The results of the first wave went clearly against the gift exchange hypothesis.

Workers who received the bonus decreased their productivity. This was most clearly the case comparing the condition in which both workers received the bonus (Double Bonus condition) and the condition in which neither received the bonus. In neither condition is there inequality, so the possible unfairness brought about by the introduction of inequality is absent in this comparison. The Double Bonus condition is the situation where we should observe the highest increase in productivity; instead, we observed the exact opposite, as productivity decreased by 15.1%. In conditions where only one worker received a bonus, we observed that workers not receiving the bonus had a relatively small decrease in productivity compared to the relevant placebo condition. This was especially the case in the Social Needs condition. This suggests that workers react negatively when wage policy is used to achieve social goals. Workers who received the bonus did not significantly alter their output, except for those in the “Productivity” condition, who marginally increased their effort.

The journal editor was as surprised as we were to find clear evidence going against the gift exchange hypothesis. They asked us for a second wave of research to (a) replicate the result and (b) investigate the possible underlying psychological mechanisms. After more than 10 years since the first study, we obtained funding from IfW for a second study. Although we kept the protocol as similar as possible to the first wave, something inevitably changed, starting with the considerably different macroeconomic situation in Colombia.

We conjectured that the absence of gift exchange may have been due to what we called a contentment effect. Especially in the Double Conditions, workers interpreted the bonus as a signal that the employer was content with their effort in the first part of the day. In particular, this would reduce their belief that they might be fired for shirking effort later in the day. To investigate these mechanisms, we introduced two short questionnaires right after the bonus was communicated and at the end of the working day. This questionnaire had to be unintrusive to avoid shifting beliefs and expectations and to ensure the effect we found in the first wave was not jeopardised. We only focused on the No Bonus and Double Bonus conditions. The results were in line with the first wave: Workers in the Double Bonus condition reduced their effort in comparison to those in the No Bonus condition after receiving the bonus. The drop in output was 8.4% - not as large as in the first wave, but still statistically significant.

We find moderate evidence supporting the validity of our explanation, as workers in the Double Bonus condition indeed expressed a lower fear of being fired compared to those in the other condition. However, this effect was not as strong as we expected, and workers did not express differing views on whether they believed the employer was satisfied with their effort. Perhaps this is because work relationships are particularly hierarchical in Colombia, leading workers to prefer not to express any judgment on their employer’s attitudes towards them.

I believe that this evidence is valuable in extending our knowledge of how human psychology impacts labour market outcomes. In the end, it seems that the firm’s profit-maximising strategy is not to pay any bonuses and to maintain an equal pay structure, a result that is in line with Thomas Bewley’s analysis. Some caveats apply: We did not study the potential incentivising effect of bonuses in inducing higher effort if pre-announced rather than handed out as a surprise. However, evidence from studies doing exactly that fails to find any positive effect of incentivisation, as the decrease in productivity by workers not receiving the bonus more than offsets the marginal productivity increase in others. This is pretty much what we also observe in our study. Ours was a one-day work relationship, so we don’t know how the results will generalise to other contexts. However, having short work contracts is the norm for the informal sector of the economy, and this approach enabled us to pinpoint the effect of bonuses without the confounding effect due to reputation. The final caveat is perhaps the most difficult to address: Would we get similar results in WEIRD countries? Of course, we cannot say anything without data. In the paper discussion, however, we make the point that Colombia scores at a level similar to Western countries in reciprocity, according to Hofstede’s cultural indicators.

This has been a decade-long effort, and I would like to thank my wonderful co-authors Francesco Bogliacino, who conceived the study with me and supervised data collection after I left Colombia, and David Pipke. who did a fantastic job in working out the theoretical model and analysing the dataset. We all contributed to writing the paper. A big big gracias to our great research assistants who carried out data collection: Laura Jimenez Lozano, who assisted us in all the 151 research sessions; Suelen Castiblanco, who acted as experiment instructor in the first wave, and Daniel Reyes Galvis, who also assisted us in the first fieldwork and worked on data. More gratitude to IfW for funding the second wave of this project and providing ethical approval.